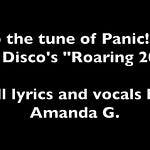

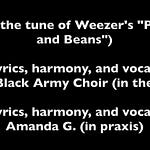

All lyrics and vocals: Amanda Griffiths

All power to this backing track

All power to MediaHuman’s YouTube to MP3 converter

All power to copyright under Creative Commons (link to license not req’d for sharing)

This one might N be SFW. I guess it depends on your W.

Notes:

This is the earliest-written song on the album, by several years (albeit recorded at the same time as the rest). The others, with the exception of “The Revolution That Couldn’t, Couldn’t” were written over the span of summer 2024 or later. This one, I wrote during my undergraduate days, on the knife’s edge of my 20s.

This track is, regrettably enough, a genuine allegory for ideological interplay as sexual foreplay. (I told you. I was barely 20. Everything I did was some flailing, tortured metaphor. It’s only gotten worse.)

It was never the right time to share it. I will not be taking further questions.

Something I realized while writing this song is that free markets are extremely feminine-coded: Contingency, momentum, spontaneity, risk, dynamism, variety, innovation.

Marxism, on the other hand, is extremely masculine-coded: Dominance, inertia, planning, order, force, stability, putting things in their place, keeping them there.

Combine the two, and you’re gettin’ dialectically nasty in the bedroom.

(NB: When I refer to things as being “feminine-” and “masculine-” coded, I am referring to their association with concepts that are culturally affiliated, however arbitrarily or cursorily, with the male or the female. Personally, I prefer not to use the terms “masculine” and “feminine” except when discussing general perceptions of qualities, without endorsing the accuracy of those perceptions.)

So, when you listen to this, you can interpret the female part as, itself, the free market. You can interpret the male part as Bolshevik policy. If that’s your thing.

Another thing I realized while recording this song is that I do not have a sexy male voice. (…I think was going for Brendon Urie?) My Berkman voice is marginally sexier, which seems fitting. That one drops in a couple more weeks.

If I were a different sort of person, I would write a screed polemicizing all Marxists as innately misogynistic for “seeking absolute domination of the Market-Feminine”—just to troll them—but I am not that sort of person. So I will write this instead, using this space as a scratchpad for various ideas (I will not write a feminist vindication of the free market. I will not write a feminist vindication of the free market. I will not write a—):

Marxian thought has, in many cases, become emasculated in the West. (I am not speaking of silly “culture war” nonsense here, but rather of the West’s treatment of and attitude towards Marxian logic itself.) This might explain my unique distaste for Western pseudo-Marxism, in part; as well as the intellectual tension I experience when reading old-school Marxian thought: Stick a gender inventory in front of me, and I’ll range anywhere from 83–92 percent “masculine”. There’s an enormous part of me that gravitates toward the myth of stability even as another part of me rushes to the precipice of every abyss it can find.

I think I understand the philosophical origins of this tension: For me, freedom is an Existential concept—it is all valuation—such that an essential element of freedom is the freedom to fabricate and fashion oneself according to one’s own restrictions. Hence the lyric, “I know about austerity”: Without agentic restriction, without agentic discipline, we cannot create any sort of meaning; since the creation of meaning requires distinction—the definition of boundaries, however ultimately (indeed, necessarily) fungible. Restriction is a radical act.

The critical thing, however, is that inasmuch as freedom is an Existential, valuative action, it is inherently individualistic: Restriction cures and curates meaning. You must take ownership of your restrictions; you must identify them and identify through them. You must individuate one another and use them to individuate further ideas. This is one of the many things Marxism misses.

What happens in the allegorical reading of this song, then, in which the ideological becomes the sexual, is that the free market is consenting: She taunts the Marxist’s monopolistic planning; she teases planning; she invites planning to do its worst. The increasingly frustrated Marxist, on the other hand—true to form—yearns to exploit the “female” market. As she indulges his fantasy, he believes he is winning—that he has dominated her, broken her, gotten inside of her—but it is he who relies on her to bear “his” creation outward. The free-market-as-female is, in other words, forever the cultivator and bearer of the progress that Marxian “masculinity” claims to own. (Compare to: Non-embargo relations between Communist and non-Communist nations.) By ironic contrast, the free market does not claim any ownership of progress. That is very much the point: The free market frees progress. She bears and releases it into the world, as its own willing, infinitely differentiating, subject.

Any good Marxist knows that you need to use the institutions of the capitalist to defeat capitalism. So does any good free market Innovationist. (Critically, for the Innovationist, “defeat” is an evolution; a radical dissolution and redemption of industrial-era capitalism’s monopolistic, centralizing tendencies.) The difference lies in the manner in which each engages the turn.

The Marxist uses the institutions of the capitalist in a way that leads him to become the capitalist—the industrial-era capitalist. His view of capitalism, even capitalism’s evolution, is bounded, as any good Marxist should understand, by the material conditions in which Marx was writing. (I’ll elaborate, for all the “his view, yes, but…”s being raised presently.)

At one time, associating property- and profit-based economic arrangements exclusively with sociopolitical oppression made far more sense than it does today: Agrarian Russia's pre-industrial land tenure systems—virtually the only consistent source of profit and economic stability for most—had been the purview of the state; and even after the Emancipation of the Serfs, land ownership still proved out of reach for the majority of peasants, whose lot it was to work the land of the owning class in exchange for a small share of the yield. The socioeconomically-fractured labor relations that constituted rural farming culture mirrored those of urban manufacturing, with seemingly intractable divisions between the working and owning classes returning vast and tangible differences in lifestyle, social access, and living conditions.

Elsewhere in Europe, the situation was much the same. Early industrial capitalist economies had cropped up in, and were therefore constructed to operate in and sustain, hierarchical, class-centric societies such as these, in which states benefitted from limiting social mobility and concentrating the distribution of capital in the hands of a few (a relic of mercantilism and of its social psychology, which mutually reinforced and were reinforced by such arrangements).

Yet, as the above suggests, these relationships were conditioned by the mechanics of the class-centric society in question rather than innate to the mechanics of non-communitarian economics itself. If man has no inherent nature, only condition, then the same must be true of any economic system (among which we may include both capitalism and Communism). Generally speaking, the oppressiveness of the market will always be a reflection of the oppressiveness of the state.

What is more, and contrary to Karl Marx's most desperate pleas against reality, a free market system that yields an unequal distribution of wealth is hardly fated to produce class-centrism. If anything, a free market society that facilitates radical social mobility renders obsolete such rigid class distinctions (beyond those imprinted by an ideological false consciousness, that is).

A free market society that facilitates radical social mobility and promotes competition also accelerates more swiftly and produces more efficiently—an imperative in the era of globalization and open trade that industrialization helped to usher forward—and this was the lesson eventually learned by many states that had, prior to and during the early Industrial Revolution, been buoyed by rigid class boundaries and high, state-sanctioned barriers to economic entry. Dismantling these barriers, often through policy changes that opened greater avenues toward wealth-building for a greater number of citizens, became vital in order for states to satisfy the incentives brought about by early capitalism. Where trading states liberalized in this way, the more primitive capitalism that had characterized the first decades of the Industrial Revolution necessarily evolved into an increasingly complex yet agile free market system; and through this system, there began to develop an even newer, multi-nodal, ever more radically-decentralizing free market culture: Innovationism.

It was an uneven, but combined, development.

Today, centralized state command of capital and labor—be it capitalist, communist, or anything besides—indulges a reactionary, romantic, conservative sentiment, being that it draws from the paradigms of production and labor that constituted the very beginnings of industrial society, which have, like all living things, evolved.

Marxism, on the other hand, remains theoretically stillborn.

This is the problem with most theories of revolution: They are usually fitted to revolution as it could unfold, and to what it could aspire, within a particular time and a particular place according to a particular person with a particular conditioning. Any attempt to realize that same image of revolution, say—I don’t know—200 years later is therefore both definitionally reactionary and born of a false consciousness that propagandizes the pseudo-revolutionary into believing that material conditions now must be, more or less effectively, what they were 200 years prior.

(“No! Not the *same*, the same! Marx *knows* that you can’t predict stuff, and…”)

Believe me: I understand that Marxists think Marx gives you a way around this. I have read many arguments, some of them decently thought-provoking, to this effect. It just so happens that Marxists think that Marx does a great many things that Marx does not, in fact, do. My point is that Marx’s theories are conditioned, not even by prescriptions, but by observations, that are so particular to the very specific material conditions of early industrial-era European capitalism that they—and every fool theorizing in his shadow—effectively attempt to strap a rubber band around the world as it presented itself to Marx in the middle of the 19th century, keep it there, and then realize a so-called revolutionary vision with such artificial, if not entirely imaginary, constraints around all temporal progress.

If that sounds paradoxical, it’s because it is. Many theories of revolution, not just Marxism, fall prey to this dilemma: The revolutionaries who would actualize them must force the world to be simultaneously the same as it was when the theorist was writing and different from what it was when he was writing, in just the way that he meant for it to be different. The attempt fails; the rubber band snaps; the center collapses; thank God; progress happens after all. But all this in spite of Marx, and all too often, after too much blood for nothing.

This is not to say that we should reject theories of revolution and revolutionary theories out of hand. It is to say that we should be mindful of past revolutionaries’ mistakes when we read, develop, analyze, and agitate in their name.

That the Marxist believes in things like a “late-stage capitalism” suggests he believes only in a capitalism that looks a certain way; a relationship between the laborer and the owner that looks a certain way; institutions of ownership and exchange that look a certain way; a theory of production that looks a certain way; under a model of individual ownership. He believes in a certain path of evolution to a certain point under and according to certain conditions—Marx’s conditions.

What I am saying is that the qualities that Marx identified as endemic to free markets were actually endemic to the relations of production of a given era. As market dynamics evolved, so did the realities and possible relations of production—surpassing a need for a state Communist alternative; and rendering any attempt to realize a state Communist alternative an inherently reactionary enterprise.

What I’m saying is that I reject Marx, in no small part, because I’ve got a little materialist in me, too.

The Innovationist, by contrast, does not believe in categorical “stages” for progress because the Innovationist rejects planning and objective pre-definition. If there ever was a pure “late-stage capitalism”, it existed no later than the 1950s; World War II perhaps marks the transition (in capitalist countries) from capitalism to early Innovationism. This transition, however, is a long march, not a moment. Presently the combination of the gig economy, decentralized financial markets, and currency competition has the potential to realize many of the objectives, in terms of human livelihood, work, and welfare, that earlier Communist writers (of which Marx was among the least popular) envisioned. We are indeed hair-splittingly close to fully automated luxury gay space Innovationism, and the most intellectually honest minds on the left and right damn well know it. It is state regulation, co-sponsored by malign actors’ (including Big Unions’) push to arrest labor automation, that most threaten this reality’s coming to fruition. Marxian capitalism, for its part, if it ever existed, no longer does—except, perhaps, in state Communist regimes. I will elaborate:

Any attempt that the Marxist makes to “use capitalism to defeat capitalism” demands that he return and restrain the capitalist model to what it was 200, 150 years ago. I will not pretend that that model was not ugly. This is one of many reasons that I see no reason to return to it out of a reactionary, romantic Marxian sentimentality. Yet Marxian methods inherently require both capitalism and capitalism’s negation, in the middle voice, to be as exploitative and brutal and objectifying, on the part of the individual worker, as the most exploitative and brutal and objectifying boogey-man image of industrial capitalism—even at the point and in the process of revolution.

As an example, consider the One Big Union model of labor. If a Big Unionist trusts you enough and/or has had enough to drink, he will speak openly of “union density” as his ultimate goal—and nothing about workers’ rights or empowerment or anything of the sort. No; he is an owner, a businessman, same as the rest; his product is the worker’s speech, outsourced to himself; and his job is to ensnare more consumers—workers—by any means necessary, even at the point of federal force. He has abandoned the grassroots for the government; he shirks truly leftist organizing tactics for the stultifying certitude of bureaucratic capture. He does not object to monopoly at all: He merely objects to corporate monopolies, and not even all corporate monopolies, mind you; but corporate monopolies held by corporations with which he does not have a contract. He objects, too, then, to gig work, to self-employment, and to local independent unions. He prefers large corporations to small businesses: Small businesses are prone to decentralized, worker-led unions; and not only does the Big Unionist know how to play with large corporations, these corporate behemoths are the very antagonists necessary to the narrative on which he survives. They are ready-made targets for his manufactured outrage against corporate glut. The corporate Big Unionist needs the cubicle farm, the nine-to-five, the human assembly line, like the pharmaceutical manufacturer needs disease.

The difference is—while the issues related to pharmaceutical companies’ enmeshment with the state are similar to those that arise from Big Unionists’ embeddedness in bureaucracy—that disease, or its possibility, has a much greater likelihood of remaining with us for far longer than the human assembly line does. If one disease is eradicated, there are other quality-of-life improvements a manufacturer can pursue—and he has financial incentives to do so. But if the traditional model of work is eradicated, the Big Unionist must fundamentally re-orient his business model—and this is a costly endeavor. If a worker becomes too free, if his life is too much improved, if he is employed too independently, the Big Unionist loses a consumer. The Big Unionist is therefore financially disincentivized from the same sort of innovation that keeps pharmaceutical manufacturers afloat, partly owing to a state-sanctioned dearth of competition—one already too pervasive in the pharmaceutical arena; and one all the worse when it comes to the market for workers’ speech. In reality, then, the corporate Big Unionist needs exploitative labor more than the pharmaceutical manufacturer needs disease.

Hence the false “paradox”, occasionally remarked upon, between the Big Unionists’ objection to corporate ownership and self-employment simultaneously. What is false here is not one or the other objection itself, but the perception of the Big Unionist’s intent. Understand this, and the paradox is not a paradox at all: The Big Unionist does not object to either model of labor—corporate ownership or self-employment—out of a concern for workers’ welfare. He merely objects to a scenario in which someone who could be paying dues, who could be buying his product, who could be giving him their money, and in the process, their power to advocate for themselves, is not.

This is precisely the behavior of an old-school factory owner, or, if you’d prefer to go back further, a sort of feudalism in which serfs pay tribute for the protection of the owner; and the state, petitioned by the owner, deliberately hamstrings serfs from extracting themselves from these relationships via policies that keep labor relations just so. It helps them; it helps the owners; little else matters.

It doesn’t help the serfs, but in the first place, the serfs aren’t directly enriching the state’s coffers in the way that the owners (or Big Union lobbies) are; and in the second, it is quite simple for a more conservatively-minded individual to make the argument that all this does, after all, help the serfs. Doesn’t it? They’re guaranteed land! They’re guaranteed protection! They’re guaranteed a living! They get a sheet cake at the end of the year! (Okay, that one’s just the Big Unions.) All they need to do is remain in that particular position, on that particular plot of land, doing the work they’re told to do, paying what they’re told to pay, and not expect too much out of the living or the life they’re guaranteed. Who says that nobody benefits from mediocrity? The status quo certainly does; and every state, no matter how revolutionary in its inception, seeks to preserve its own status-based status quo.

When such a system of organized labor is the absolute norm, it can be almost impossible to conceive of any truly radical alternative. Ultimately, not even the Revolutionaries could.

This is because the radical alternative is never created by one man, or one group of men. It is created by the dynamics of free exchange, which man can neither plan nor predict. That is the point.

My understanding is not that most Big Unionists began with such overtly malign intentions as elaborated above. Rather, materialist logic dictates that anyone who proceeds according to this ridiculous “negation of the negation for Hegel’s own sake” model of combat is fated to become his enemy sooner rather than later and destroy only himself in the process.

It is rather strange: One would expect a halfway decent materialist to recognize that the material institutions and methods to which you comport yourself will condition you in just such a way; so that if one adopts or usurps the institutions of the capitalist, one shall be conditioned according to the profit-seeking, exploitative motives that incepted and sustain those capitalistic institutions in fairly short order. He will begin to act like a capitalist, think like a capitalist, want like a capitalist, and treat his workers like a capitalist—with the exception that if the “one” in question is a state or deputy thereof, and therefore has the capacity to subdue any competing model of labor or way of life with violent force and institutions that legitimate his actions, he has little incentive to do much at all in the way of appeasing laborers, so long as he keeps them, in whatever mode, from violently revolting.

A state with absolute ownership of productive capacity is a corporation with an absolute monopoly on the laborer. The only difference is that the state has guns and courts to place before the factory doors; and cages to place beyond them.

Oddly, the Marxist’s much-ballyhooed materialist acuity stops just short of reaching this insight.

The Marxist’s reading of progress is, in sum, extraordinarily unidimensional and static. In other words, Marxian progress is not progress at all—not even in theory.

Innovationism uses the institutions of the capitalist by decentralizing them, taking those of their elements that accord themselves with innovationism’s own ideals, opening them to all, and using the infinitely iterative recombination of their disparate parts to create new institutions, new modes, new possibilities. The Marxist uses the institutions of the capitalist in a primitive-capitalistic manner. Innovationism does so in a dynamic, progressive manner.

Back to the music: This discrepancy in both process and product of Marxian versus Innovationist methodology is also reflected in the contrasting rhythms of either part’s final spoken-word stanzas (Yes, this was, humiliatingly, all intentional): Innovationism, in true infinitely-iterative fashion, begins producing ever more quickly, spinning out ever more syllables per line. The more it realizes itself, the more swiftly it continues to realize itself. The Marxist, by contrast, becomes ever more bureaucratic, dutifully plodding along: “I’ll live rent free in your head” (7) / “Fuck you ‘til you’re seeing red” (7), alongside Innovationism’s “I’m gonna sanction you all night” (8) / “You’ve never felt a blockade this tight” (9). Thereupon the Marxist actually slows down, still doing no more than reproducing earlier patterns—“Rise up from below you” (6) / “Then I’ll overthrow you” (6)—whereas Innovationism proceeds ever more quickly, simultaneously differentiating within itself (an expression of decentralization) and building on itself anew—”Not gonna beat me (5), you won’t defeat me (5)” (10) / “Only complete me (5) when you can compete with me (7)” (12).

Any good Machiavellian knows, finally, that so long as your enemy relies on you to sustain themselves—even if they think they are defeating you—they can never truly defeat you. They will either become you, or they will succumb to you. The Marxist cannot realize Marxism without the free market; yet the free market can create without Marxism. Nevertheless, free market theory does not call for the defeat of voluntary collectivist systems; whereas Marxian theory surely calls for the defeat of all voluntarist economies (however haplessly much it negates that mandate in praxis).

Hence the lyric: “I’ll be your infinite war, your muse and your villain”. The Marxist just doesn’t know how to quit the market. He thinks he’s pinned her down, when really, he’s tied himself up—and ultimately, his only release lies in absolute fantasy.

Lyrics: “Extraindustrial”

[M]

I’m about to rise up, it’s a revolution

I’ve got a lot of wealth inside that needs redistribution

The way you’re looking at me’s giving me hyperinflation

Call me proletarian, cause you’ll be taking my dictation

[FM]

This an opportunity zone

Welcome to the wild west

If you work it, it’s your own

I’ll consume what you’ll invest

I know about austerity, my interest rates are going up

I feel your solidarity, here’s what you get for showing up

My invisible hand

Wrapped around your sector

Haunt you like a specter

I supply, you demand

Fuck the regulation

This is innovation

[M]

You’re the site of my coup

I’ll be your negation

You’ll be my negation

I’ve got to p-pass through you

Is this speculation

[FM]

I’ll be your infinite war

Your muse and your villain

I’m free enter-prise

And this class is ready for you to analyze

[M]

Petit b-bourgeoisie

Wanna fuck you up

Seize your means of production

[FM]

Dirty C-c-commie

Show you where to park it

Come and free your market

[BOTH]

It’s so Hegelian

What we’re exchanging

It’s super-capital

Extraindustrial

[FM]

Your MACD’s feeling strong

Stake out a position

Call in competition

I feel you going long

First I’m gonna pump it

Then I’ll let you dump it

[M]

You got me working my way

Through your institutions

I’ll strike from inside

And I guarantee the real me’s never been tried

Petit b-bourgeoisie

Wanna fuck you up

Seize your means of production

[FM]

Dirty C-c-commie

Show you where to park it

Come and free your market

[BOTH]

It’s so Hegelian

What we’re exchanging

It’s super-capital

Extraindustrial

[M]

Are you a commodity?

‘Cause I fetishize you bodily

And you’ve got value I can’t see

[BOTH]

Don’t say that I didn’t warn you

‘Cause I don’t wanna reform you

I’ll finish you or you’ll finish me

[M]

Secret is this never stops

From the bottom to the top

We’ll just keep on switchin’ our positions ‘til we’re swallowed up

[FM]

You’ve already become what you ran inside when you’d begun

Showed you how it’s done and that’s the slickest trick to how I won

[M]

I’ll live rent free in your head, fuck you till you’re seeing red

[FM]

I’m gonna sanction you all night; you’ve never felt a blockade this tight

[M]

Rise up from below you, then I’ll overthrow you

[FM]

Not gonna beat me, you won’t defeat me, only complete me if you can compete with me

[M]

Petit b-bourgeoisie

Wanna fuck you up

Seize your means of production

[FM]

Dirty C-c-commie

Show you where to park it

Come and free your market

[BOTH]

It’s so Hegelian

What we’re exchanging

It’s super-capital

Extraindustrial

[FM]

-al, -al, -al, -al

[BOTH]

Extraindustrial

[FM]

-al, -al, -al, -al

[BOTH]

Extraindustrial

It’s so Hegelian

What we’re exchanging

It’s super-capital

Extraindustrial